Fables and Morality Tales

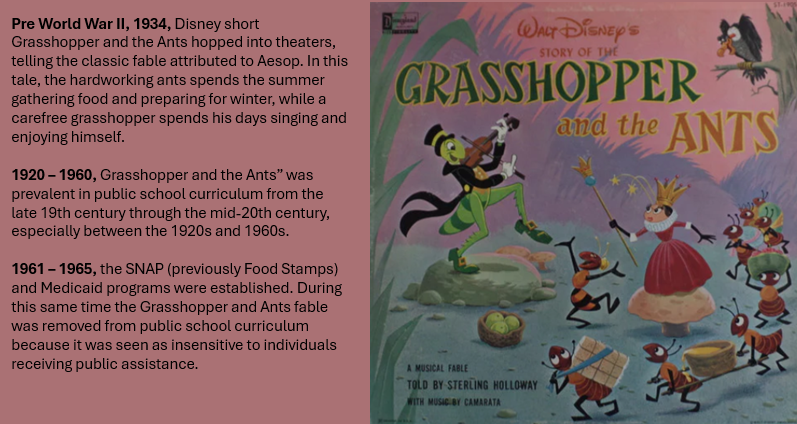

Benjamin Franklin was a strong advocate for fables and morality tales as effective tools for teaching virtue and practical wisdom to ordinary people. He believed that moral instruction needed to be accessible, entertaining, and practical rather than abstract or preachy, making fables an ideal medium for reaching the common folk of America.

Franklin extensively used the fable format in his own writings, particularly through his famous creation Poor Richard's Almanack, which contained proverbs and brief moral lessons that functioned much like condensed fables. He was deeply influenced by Aesop's Fables and often employed similar techniques—using fictional characters, animals, and allegorical situations to convey moral truths. His essay series "The Busy-Body" featured fictitious characters like Ridentius, Eugenius, and Cato who embodied different moral lessons, demonstrating his belief that character-driven narratives were more effective than direct sermonizing.

Franklin understood that fables worked because they made moral lessons memorable and applicable to real-world situations. He recognized that "The People heard it, and approved the Doctrine, and immediately practiced the contrary," showing his awareness that moral instruction needed to be engaging and reinforced through storytelling rather than simple proclamation. His approach emphasized that moral tales should teach virtues like industry, frugality, and honesty in ways that demonstrated their practical benefits, not just their abstract goodness.

Franklin promoted the printing press specifically as "a device to instruct colonial Americans in moral virtue," viewing the widespread distribution of fables and moral tales as a public service and a way to build the character foundation necessary for a democratic society.